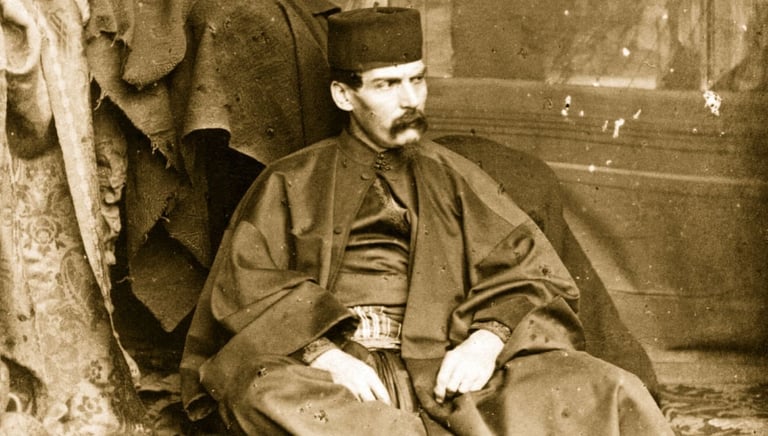

Sir Richard Francis Burton

Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton was no ordinary Victorian gentleman. A fearless explorer, master linguist, and legendary rogue, he ventured where no European had dared, often in disguise and at great personal risk. From sneaking into Mecca under penalty of death to dueling over the honor of a pet monkey, Burton’s life was an unrelenting adventure. With a sword in one hand and a pen in the other, he documented his wild exploits in works that shocked, enlightened, and enraged his contemporaries. His legacy remains one of the most intriguing—and outrageous—of the 19th century.

2/10/20253 min read

The Swashbuckling Scholar Who Drank, Dueled, and Discovered

Few men have lived lives as daring, scandalous, and outright bizarre as Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton. Explorer, linguist, spy, swordsman, and cultural chameleon, Burton was a Victorian-era adventurer who made Indiana Jones look like a timid librarian. His exploits took him from the heart of Africa in search of the source of the Nile to the secret inner sanctum of Mecca—disguised as a Muslim pilgrim at risk of being beheaded if exposed. His wit was sharp, his sword sharper, and his ability to annoy the British establishment even sharper still.

A Linguistic Prodigy With a Flair for Disguise

Born in 1821, Burton mastered over 40 languages and dialects, which came in handy when he infiltrated cultures that were, to put it mildly, unwelcoming to outsiders. His most famous undercover mission was his pilgrimage to Mecca in 1853, an endeavor chronicled in "Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al-Madinah and Meccah." If caught, he wouldn’t have just been politely asked to leave—he’d have been torn apart limb by limb. Burton took this in stride, meticulously studying Islamic customs and even undergoing an operation to alter his circumcision so he could pass as a native.

To test his disguise, he once walked into a random shop in Cairo and loudly insulted the Prophet Muhammad. When no one batted an eye, he figured his cover was solid. (Burton, "Personal Narrative," Vol. 1, p. 237)

The Man Who Fought Everything—Including Monkeys

Burton’s adventures weren’t just about slipping unnoticed into forbidden places. He also had a habit of getting into fights. He famously dueled at least five times while stationed in India, once over a perceived slight involving a pet monkey. (Burton, "Goa and the Blue Mountains," p. 87). He studied local martial arts, including the use of the talwar, an Indian curved sword, and was rumored to be one of the deadliest swordsmen in the British army. His military superiors, however, were less impressed with his skills and more concerned with his habit of dressing as a native and disappearing into the city for days at a time.

Speared in the Face—And Still Kept Talking

Burton’s most famous injury came during an ill-fated expedition to Somalia in 1855. While camping near Berbera, his party was attacked by Somali warriors, and Burton took a javelin straight through the cheek, the point coming out near his ear. He survived, of course, and later described the attack in graphic, almost gleeful detail in "First Footsteps in East Africa." The wound left him with a fearsome scar, which he wore like a badge of honor—he often used it to intimidate people at Victorian dinner parties. (Burton, "First Footsteps in East Africa," p. 312)

The Nile? Found It (Sort Of)

In the 1850s and 1860s, the race was on to locate the source of the Nile, and Burton, never one to pass up an opportunity for adventure, threw himself into the quest. He teamed up (and later fell out) with fellow explorer John Hanning Speke, trekking through East Africa in what can only be described as an extended fever dream of dysentery, insect bites, and mutual loathing.

They eventually reached Lake Tanganyika, but Speke later claimed Lake Victoria was the true source—without Burton, who was too sick to dispute it. Their feud escalated into one of history’s greatest explorer rivalries, culminating in a planned public debate in 1864. Tragically (or suspiciously?), Speke died from a gunshot wound the day before. Officially, it was a hunting accident. Burton, who had openly ridiculed Speke’s claims, reportedly took the news with an unreadable expression and a very large drink. (Burton, "The Lake Regions of Central Africa," p. 415)

Erotic Anthropology and the Kama Sutra Scandal

Burton’s fascination with foreign cultures extended beyond geography—he had an insatiable curiosity about their, shall we say, bedroom customs. He translated the "Kama Sutra" and "The Perfumed Garden," causing a scandal so enormous that Victorian England practically had a collective fainting spell. The British government tried to suppress his work, but Burton, ever the rogue, managed to privately distribute copies through his secretive Kama Shastra Society. (Burton, "The Kama Sutra of Vatsyayana," Preface, p. vii)

The Final Chapter: Death and a Literary Bonfire

After decades of adventure, Burton died in 1890, leaving behind a body of work as vast as his travels. His widow, Isabel Burton, horrified by his racier writings, burned many of his unpublished manuscripts—an act that still makes historians and adventure lovers wince in collective agony.

Burton’s legacy, however, is indestructible. He wasn’t just an explorer; he was an intellectual insurgent, a man who reveled in shattering Victorian conventions while mapping uncharted lands. He remains one of the most fascinating figures of the 19th century—a man who fought duels, drank deeply, loved passionately, and wrote about all of it with an unflinching, mischievous wit.

One thing’s for certain: the world will never see another quite like him.