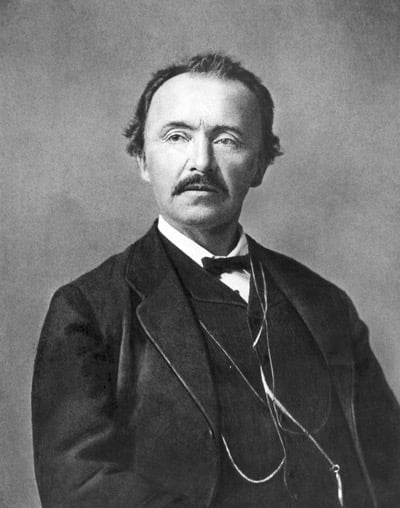

Heinrich Schliemann

Was Troy just a myth? For centuries, scholars debated whether Homer’s Iliad described real events or pure legend—until a determined German businessman-turned-archaeologist set out to prove its existence. Heinrich Schliemann, an eccentric and self-taught explorer, defied academia, dug where no one else dared, and uncovered what he claimed to be the lost city of Troy. His dramatic discoveries, controversial methods, and larger-than-life personality made him both a pioneer and a renegade in the world of archaeology. This is the story of his obsession, his triumphs, and the strange, sometimes comical moments that defined his extraordinary journey.

2/9/20254 min read

Heinrich Schliemann: The Man Who Found Troy

Heinrich Schliemann, the eccentric German archaeologist and self-made millionaire, became one of the most controversial figures in the history of archaeology. Born in 1822 in Neubukow, Germany, Schliemann was fascinated by Homer’s Iliad from a young age. While scholars debated whether Troy was a myth or reality, Schliemann was convinced that Homer’s epic described real events and set out to prove it. His travels took him across Russia, Greece, and Turkey in his quest to uncover the lost city of Troy. His findings, documented in his works such as Trojanische Altertümer (Troy and Its Remains), reshaped our understanding of ancient history.

A Man of Adventure: From Merchant to Archaeologist

Schliemann’s path to archaeology was anything but conventional. Before becoming an explorer, he was a successful businessman, making a fortune in trade across Europe and Russia. His financial success allowed him to retire early and pursue his true passion—proving the existence of Troy. In his memoirs, he wrote:

"As a child, I read Homer’s lines about Troy’s walls, and I swore to myself that one day I would find them. Nothing could stop me—not doubt, not poverty, and certainly not academia’s skepticism." (Schliemann, Trojanische Altertümer, p. 5)

Despite having no formal training in archaeology, Schliemann was determined. He learned Greek and Latin to read ancient texts in their original form and embarked on an expedition to Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), armed with little more than Homer’s descriptions and an unshakable belief.

Discovering Troy: The Excavation of His Life

In 1871, Schliemann began digging at Hisarlık, a site he believed matched Homer’s Troy. His unconventional methods—often destructive by modern standards—led to the dramatic discovery of what he claimed to be the lost city of Priam. Among his most famous finds was a collection of golden artifacts he called “Priam’s Treasure.” He later smuggled these artifacts out of Turkey, causing an international scandal.

One of the most amusing moments of his career came when he tried to impress his wife, Sophia, by dressing her in the newly discovered “Jewels of Helen.” He proudly took photographs of her wearing the ancient gold, declaring, “My beloved wife, the modern Helen of Troy!” (Schliemann, Troy and Its Remains, p. 89). Scholars were horrified, but the image became legendary.

Despite his triumph, Schliemann faced criticism. Many scholars accused him of destroying layers of historical evidence by digging too hastily. In his writings, he defended himself passionately:

"History belongs to those who dare to uncover it. If some stones must be moved for the truth to emerge, so be it!" (Schliemann, Trojanische Altertümer, p. 112)

Emotions and Motivations: The Obsession with Troy

Schliemann’s passion for Troy bordered on obsession. He was driven not just by historical curiosity but by a personal mission to prove Homer’s epics were based on reality. His writings reveal a man consumed by a singular goal:

"I have stood upon the ruins of Troy, and I have felt the spirits of Hector and Achilles whispering through the wind. The dream of my childhood is now real." (Schliemann, Troy and Its Remains, p. 150)

However, his quest for fame sometimes led him to exaggerate or misinterpret his findings. For instance, he initially believed he had uncovered the actual palace of King Priam, though later research suggested he had misidentified the layers of the site. Nonetheless, his determination laid the foundation for future archaeological discoveries.

Challenges and Struggles: Academia vs. the Maverick Explorer

Schliemann’s unorthodox approach did not sit well with the academic community. He was often at odds with established scholars, who criticized his lack of formal training and reckless excavation techniques. He, in turn, dismissed them as armchair intellectuals who lacked the courage to dig for the truth.

One particularly strange episode occurred during a heated argument with a rival archaeologist in Athens. When challenged about his lack of formal education, Schliemann reportedly pulled out a copy of The Iliad and, in perfect ancient Greek, recited entire passages from memory. The stunned scholars could only watch in silence as he declared, “Homer is my professor!” (Schliemann, Troy and Its Remains, p. 202).

Beyond Troy: Travels in Mycenae and Beyond

Schliemann didn’t stop with Troy. His travels led him to Mycenae in Greece, where he unearthed the famous Mask of Agamemnon, an intricately designed gold funeral mask. Upon discovering it, he excitedly wrote to the King of Greece, “I have gazed upon the face of Agamemnon himself!” (Schliemann, Mycenae: A Narrative of Researches, p. 55). However, modern archaeologists later determined that the mask predated Agamemnon by several centuries.

His passion for archaeology also led him to Egypt and other parts of the Mediterranean, always searching for links to the Homeric past. He recorded his journeys with great enthusiasm, though his tendency to embellish sometimes made his accounts more dramatic than factual.

Legacy: A Controversial but Pioneering Figure

Despite his flaws, Schliemann’s impact on archaeology is undeniable. He proved that ancient myths could have real historical foundations, inspiring future archaeologists to take literary sources seriously. His discoveries at Troy and Mycenae remain some of the most significant in the field.

His writings, particularly Trojanische Altertümer and Troy and Its Remains, continue to offer fascinating insights into his methods, motivations, and the spirit of adventure that drove him. Though criticized for his reckless excavation style, he paved the way for modern archaeology, showing that the past could be uncovered if one dared to dig deep enough.

Schliemann’s life was a blend of scholarship, showmanship, and sheer determination. He once wrote, “If I have erred, let history judge me. But let no one say I did not seek the truth.” (Schliemann, Troy and Its Remains, p. 234). And for better or worse, he found it.